Has the new ISP in town lifted the veil? My thoughts on trialing Hey.com

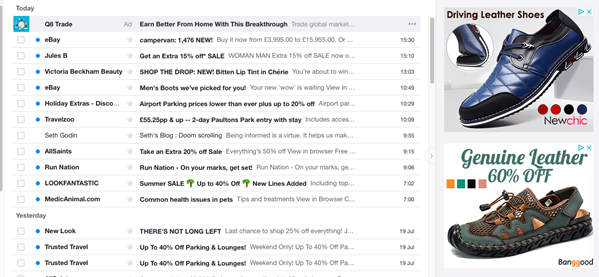

Historically, ISPs have kept the way that they operate a closely guarded secret. Sure, we could make a few educated guesses drawing on what we've learned from testing, but could any of us say for sure why (for example) Gmail sends some emails to 'Promotions' and others straight to the inbox?

Like Colonel Sanders’ spice blend, it’s always been a very secret formula.

However, a new ISP launched in June looks set to make some startling changes to this cloak-and-dagger way of operating.

Hey.com launched in June. It’s a new email service from Basecamp, and from the second it went live it was making waves in the world of email.

What's the big deal? And will Hey's new formula work? I received early invite-only access. Here are my thoughts:

What's different about, Hey?

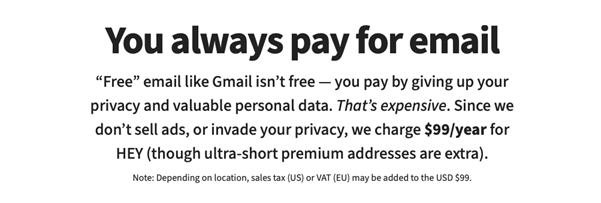

Hey is basically an email service and an email client rolled into one. It’s available on a subscription basis (currently $99 per year - more if you want a username with three or fewer letters), and will only work with @hey.com email addresses. It was initially invite-only and Basecamp CEO Jason Fried claimed that hundreds of thousands of people requested access. Now anyone can get a free trial.

Hey’s biggest (and most controversial) selling point is its drive towards total transparency. For example, Hey:

- Blocks open-tracking pixels (Hey refers to these as ‘spy’ pixels).

- Makes all attachments visible in one place.

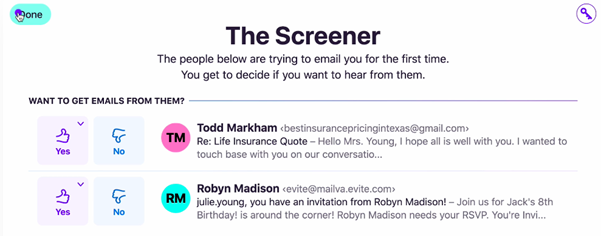

- Makes you choose Yes/No for everyone that’s emailing you for the first time via a ‘Screener’.

- ‘Names and shames’ senders who use spy pixels.

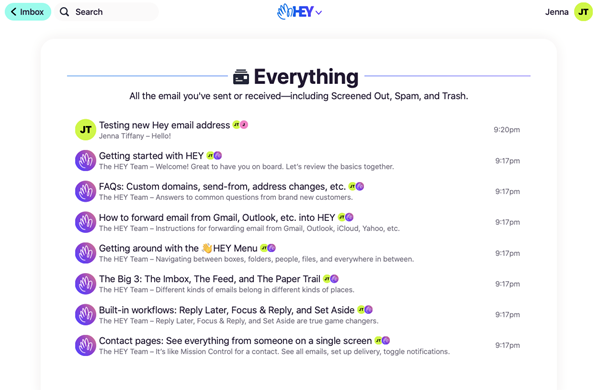

It’s also annoyed many grammar lovers by calling its inbox an 'Imbox' ('Im' for 'Important', according to Fried) - but whether or not that's a make or break issue remains to be seen.

What’s the big controversy?

It’s rare to hear Hey.com mentioned without some association with its controversies - most of which are centered around their transparency drive.

Hey’s manifesto focuses hard on transparency and control. As they put it:

“You deserve control over who can email you. You deserve to read your email without a marketer looking over your shoulder. You deserve an ad-free Imbox. And you deserve a company, and a product, with interests aligned with yours.”

One of the most controversial ways they’re achieving this aim is through disabling spy pixels - to us email marketers this is the tracking pixel.

Hey believe that spy pixels represent a massive violation of privacy, and they want that to change. So much so that they will not only actively block spy pixels from sending any information back to the marketer at the other end of the email - they will also ‘name and shame’ senders who use spy pixels by alerting users every time they discover a pixel in an email and what the pixel is tracking.

![]()

I spoke with several email geeks about this, and Chris Byrne from Sensopro said:

"Hey.com is timely, and an ESP should have nothing to fear. Yes, they will call out the tracking pixel, but we think that's a good thing. David Hansson (@DHH) was very supportive of our Do not Track initiative:

Most of us accept that the spy pixel is useful for tracking and gathering data on user activity. But are we transparent with recipients that we are monitoring their user behavior? Is it obvious? Are we able to provide the option for subscribers to manage the tracking of their behavior? Does the ESP we use enable that? These are all questions that we should start asking and most importantly, what more could we do in this area as an industry to be more transparent?

Then there’s the ‘Screener’.

The ‘Screener’ is an interesting concept. Rather than deciding via that mysterious ISP formula where to send new emails, every email from a new sender lands in the ‘Screener’. The customer then has the choice of where to consign emails from this sender.

So far as transparency goes, this is a huge step forward - and could have significant implications for email marketing if it catches on. The focus would be mostly on appealing directly to the customer rather than considering the screening of the ISP. We can tailor everything to appeal directly to the customer, and let them choose whether or not they want to hear from us.

On the other hand, it's a considerable amount of manual work for the customer. I can't see people wanting to 'screen' hundreds of emails per day. I'd get frustrated with that kind of thing - and I live in the inbox! A nice-to-have feature but not one I would want to spend hours on configuring each day.

So dedicated are Hey to providing a fully controlled and transparent email experience that they’ve even gone head to head with Apple, accusing them of being ‘anti-competitive’ and ‘using their power of monopoly’ to run their app store in an untrustworthy manner.

Whether or not that's a fair assessment, it's clear that Hey is deadly serious about their manifesto.

My experience with Hey

As Hey rolled out and the waves of controversy broke around it, I found myself intrigued. For years I’ve been urging for greater customer control in email marketing, and it looked like Hey was doing everything that we say good emailers should do.

Lucky enough to receive an early access code, I joined to see what all the fuss was about.

My initial impression was good. The user interface was clear, although you are forced to go through the step-by-step guide to their Imbox - frustrating if you just want to dive straight in! I tested a few emails, received Hey's six welcome emails which felt counter to their ethos and service proposition of 'email for the customer, not the brand', and experimented for a while.

It wasn’t bad. The screener concept definitely provides users with more control and I do think that is an interesting concept but not something I would want to spend time configuring.

It wasn’t bad. The screener concept definitely provides users with more control and I do think that is an interesting concept but not something I would want to spend time configuring.

But have I been back there? Am I a frequent user?

No.

What’s stopped me?

To be frank, I do not feel that Hey is offering enough to justify me switching my existing system across. And this is more than switching to a different mailbox provider; this is an entirely new inbox experience.

As much as I currently avoid logging into my personal inbox due to the poor experience, it would take time and be a hassle to make this switch. Everything is linked to my primary email address and, honestly, I don't think that the benefits of Hey are great enough to bother.

Sure this is a new way of managing my inbox, but I'm not going to spend the time to configure it. Would a less frequent user of email and a non-marketer be more open to using email in this way? Yes, most likely, especially if their experience with email marketing has been a bad one. And would more users do so to get away from ads in the inbox?

A more automated way to learn from a few user inputs to then proceed to make those changes for you would be something I would bother with, but for me, I feel it's not intuitive enough with too many settings to configure.

If I have to read a manual on how to use a new device, I don't bother. I just jump right in using it, and if it's then not working as expected, I might then succumb to diving into the manual, but only when you have to.

This, for me, is the same experience.

I don't need a manual for email, and if it has so many options that you have to 'learn it.'

I’m already switched off.

But then again, I don’t think a 14-day trial is a long enough period for users to get to grips with this new service. I would have welcomed more time. More time to see if I could switch my existing service and if it would make my life easier.

It was also easy to forget about the service after a while as I didn't add a secondary email address for notifications and I suspect many other users do the same. For me, it's not built into my current day to day email flow. Well, not yet anyway.

What about the subscription?

Hey are not the first subscription-based email client, and they won’t be the last. Ultimately the subscription is to pay for the new imbox service with the premium option for a shortened email address. Or as Hey describes it:

Is email the new web domain?

But the way they’re using the formula does raise some interesting questions about the intersection between email addresses and web domains.

Currently, web domains are sold (and sometimes even auctioned) to the highest bidder. The web is full of domains sitting empty, waiting for someone to offer the right price. When email addresses are sold in the same way, could we end up with a similar situation? Hundreds of unused addresses sitting around, waiting for the right buyer? Especially when after the 14-day trial Hey enables you to purchase your email address for you to keep forever, even if you didn't renew after the first annual subscription. Would you buy an email address in your name so that no-one else could have it? For those of us that work in email, the answer is a probable yes, would I? I have seriously debated it. It's a one-off cost to keep it forever.

If many others think the same about purchasing the email address to keep but not us, what does that mean for ISPs? 'Empty' addresses have traditionally been a problem when they begin acting as spam traps. Will we see a lot of Hey email addresses used in that way in the coming years?

Of course, this should not be a problem for those who gather their lists ethically and with full transparency - which brings us (again) back to Hey’s push for greater customer control over data.

Is Hey the future of email?

I don’t think that Hey is the present of email. But it might be the future. Or, at least, an influence on the future of email.

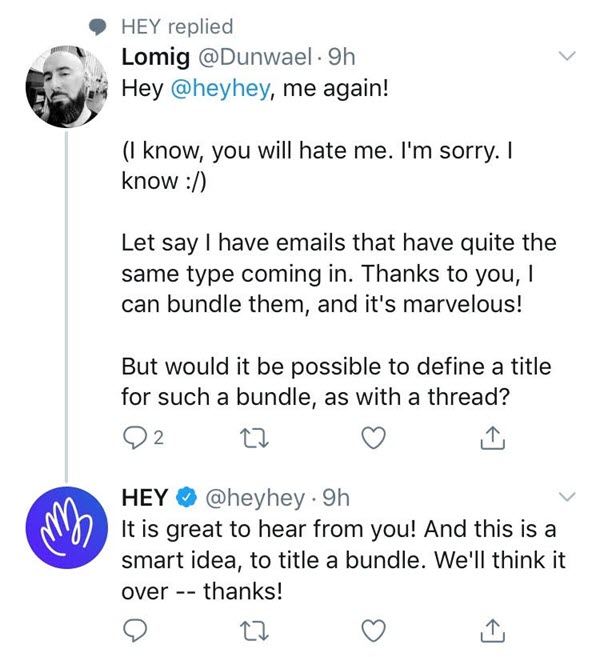

Hey's response to customer feedback is close to immediate, and each response on social media is tailored. They do seem dedicated to the personal experience and privacy of their customers across all channels (with a few exceptions - like those welcome emails I mentioned earlier). From a customer point of view, this is very empowering.

From a marketing point of view, Hey raises a lot of interesting questions. For example, blocking spy pixels means that open rates and clicks won’t be measured in the way that we’re used to.

We’ve been relying on these metrics for years. Losing them could wipe out a lot of data at a stroke - data that we use to tailor our customers’ experience and show content that’s relevant to recipients. While this isn’t always obvious from a customer point of view, the customer experience could ultimately suffer from a lack of tracked data.

However, the issues of customer privacy, transparency, and control are essential to consumers. Hey isn't the first to make this clear, by the way. We've known for years that customers want to feel more in control of their data. Just look at the public response to the GDPR back in 2018.

This is something that, as an industry, we should be discussing a lot more and an area I am passionate about in defining a solution. Hey have realized that it’s time to explore alternative approaches - and they won’t be the first. If we as marketers don’t work with ESPs to find a way to put customers back in control of things like data tracking, then ISPs like Hey will remove the choice from us.

Closing thoughts

Change is never easy, but a lot of good things can come from it.

This new entrant in the email space is bringing with it exciting concepts that have worked well for other channels. If they can be applied successfully to email, that could have huge positive implications.

Will it work? I tend to think that anything is possible if we put our minds to it fairly and openly. How we manage an uptake in hey.com subscribers that block the tracking pixel remains to be seen.

One thing, however, is for sure: Hey is very, very serious about their entrance into email.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

Jenna Tiffany is Founder & Strategy Director at Let'sTalk Strategy providing strategic consultancy services across the digital marketing mix. Jenna is a Chartered Marketer and elected Fellow of the IDM with over ten years’ marketing experience across both B2B and B2C. Jenna has consulted with brands such as Shell, Hilton and World Duty Free to name a few on digital and email marketing strategy.

Jenna Tiffany is Founder & Strategy Director at Let'sTalk Strategy providing strategic consultancy services across the digital marketing mix. Jenna is a Chartered Marketer and elected Fellow of the IDM with over ten years’ marketing experience across both B2B and B2C. Jenna has consulted with brands such as Shell, Hilton and World Duty Free to name a few on digital and email marketing strategy.